The (surprisingly long) history of electric vehicles

Electric vehicles (EVs) have been in existence for almost 200 years and pre-date internal combustion engines. Elon Musk may have captured imaginations, headlines and a fortune with his Tesla electric cars, but the reality is that EVs were on our roads and rails long before Henry Ford’s affordable cars revolutionised travel. Here we look back on the history of EVs.

Back in the 1950s it was Henry Ford’s cars that won mass appeal and it’s taken more than 60 years, and the rise of affordable renewable energy, for EVs to be back in the race. The journey to mass adoption of EVs has sped up dramatically with the UK Government's ban on sales of new petrol and diesel cars by 2030. Decarbonising cars is an essential component to reaching net zero, as transporting people and goods is responsible for around 28% of current UK carbon emissions.

Experimental EVs in the 1820s and 1830s

The earliest form of EV was created in 1828 by Hungarian Anyos Jedlik, who powered a small model carriage with an electric motor.

The 1830s then saw a flurry of activity, with electric vehicle experimentation and incremental developments.

In Scotland, inventor Robert Anderson created a basic electric carriage, as did a Professor Stratingh of the Netherlands. Across the Atlantic, Thomas Davenport of Vermont made a similar contraption, but his car ran on a short, circular electrified track.

The first electric locomotive

With the growth of the steam railways, attention turned to building a full-size electric-powered locomotive. The first was built by another Scotsman, Robert Davidson of Aberdeen, in 1837 and was powered by galvanic cells.

Davidson, a chemist, then went on to create a larger version named Galvani, which was shown off at a Royal Scottish Society of Arts Exhibition in 1841. Galvani weighed over 7000kg and managed to haul a load of 6100kg at a speed of 6.4km per hour during trials. But its limited battery power meant it was never a contender against steam-powered trains.

Interest in electric trains continued and patents for the use of rails as conductors of electric current were filed in England in 1840 and in the US in 1847.

Moving onto electric ‘cars’

For the first invention that resembled an electric car, with the scope to transport humans on roads not rails, we need to head to the streets of Paris in 1881. There, Gustave Trouve took a small electric motor developed by Siemens, improved its efficiency, used a recently-developed rechargeable battery and added it to a tricycle. Sadly for Trouve a patent was not forthcoming, although he did go on to invent the outboard motor for boats.

It took until 1895 for the a ‘production EV’ to be made – led by British inventor Thomas Parker, who was also responsible for electrification of the London Underground system.

Parker might well have been something of an early eco-warrior, as it’s believed his concern about smoke and pollution in London drove his interest in developing electric vehicles.

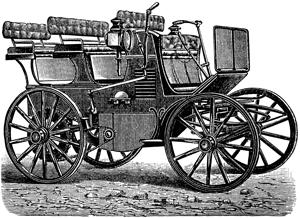

Another promising innovation came from William Morrison of Iowa, who created the US’ first electric ‘car’ around 1890; a wagon that could carry up to six passengers at a speed of 23 km/h.

By the final years of the 19th Century, electric trains were being used to transport coal from mines, electric taxis – nicknamed hummingbirds, due to the humming sound they made – were in use on the streets of London and EVs held various speed and distance records.

Perhaps the most exciting and daring of these was the breaking of the 100km/h barrier in April 1899 by Camille Jenatzy, in his rocket-shaped vehicle called Jamais Contente.

Surging popularity in the early 20th Century

While widespread adoption of EVs was initially hampered by a lack of electrical infrastructure, as homeowners embraced electrification so came a surge in ownership of EV cars in the early 1900s. Remarkably, according to Encyclopaedia Britannica, at the start of the 20th Century there were 33,842 cars registered in the US and 40% of these were steam-powered, 38% were electric and only 22% fuelled by gasoline.

...at the start of the 20th Century there were 33,842 cars registered in the US and 40% of these were steam-powered, 38% were electric and only 22% fuelled by gasoline.

Early solutions for range anxiety

An exchangeable battery was the solution to range anxiety (worrying your EV’s battery won’t last a journey and you might not be able to recharge it) provided by a joint venture between the Hartford Electric Light Company and General Vehicle Company (part of General Electric) from 1910 to 1924.

Customers would buy a vehicle without a battery and then use exchangeable batteries that were switched over as needed.

Usurped by the combustion engine

Despite this early excitement, by the late 1920s the internal combustion engine (ICE) car was winning the race to dominate vehicle sales. Top of the list of factors was the discovery of petroleum reserves, which led to a drop in the price of fuel for ICEs. Improvements in road networks meant drivers wanted to travel further than the limited range that EVs allowed. Fundamentally, ICE cars could simply travel longer distances, at faster speeds and for a lower cost.

EVs back in front

A century on, EVs are taking pole position on our roads once more. Today EVs can travel at faster speeds, longer distances and at an increasingly lower cost throughout their lifetime, when compared to costly petrol and diesel refilling. And soon the main barrier to EV uptake – range anxiety – will be also relegated to history with the Government’s Rapid Charging Fund, which will help networks, like National Grid, provide the underlying infrastructure for ultra-rapid charging across the strategic road network.

Nearly two hundred years on from their invention, modern EVs are once again symbols of the future.

Myths and misconceptions about electric vehicles